My name is Renee Bornstein, nee Koenig. I was born in Strasbourg in 1934. When I was five years old, I moved with my parents, my elder sister, Helen, and my younger brother, Joe, to the small town of St Junien, thirty miles from Limoges.

Koenig family, Renee is the child in the middle

Life changed. The following year Nazi’s occupied France. Life for the Jewish people became more difficult. As well as restrictions on our daily life, we lived with constant fear of arbitrary round ups by the Germans. People vanished without warning. One day a friend would be at school, the next they would be gone. Whenever my parents were alerted to the news that the Nazis were about to make another sweep of the village, they had no choice but to look for hiding places, wherever they could find them. At a moment’s notice, my parents would rush us out from our beds to flee to barns, farms, convents, even the cellar of a local chapel, so that we would not be caught. It is impossible to imagine how I, a child of just eight, felt, huddled in a darkened attic, or a barn, unable to make a sound. Even a creak in the rooms above or below heralded the possibility of discovery, or even betrayal.

As the Nazi grip tightened its grip over occupied France, it became clear to my parents that they could no longer reply on this haphazard hope for survival. By the end of 1943, Jewish organisations worked secretly and tirelessly to set up networks to save children and babies. My parents made the agonising decision to send us three children away to Switzerland. We were given false papers and would travel as part of a group of other so called non Jewish children. We were claiming to travel to a holiday camp in Switzerland to escape the bombing. First of all we were taken to the town of Limoges and, together with two other children, were hidden in a Catholic convent for two weeks. Peering through a crack in the window, I remember a large number of SS milling in the streets below. For years, when I saw a man in uniform, after the war, it would send shivers down my spine. We children were woken each morning at 06:00 for prayers in the chapel, then we were told to busy ourselves by picking asparagus in the gardens of the convent. One of the nuns said to me, “if Moses would have known how good ham is, he would have let you eat it”. And another said to me, “The way things are going, you know you Jews are going to die. If you’re going to be baptised you will go to paradise. If you stay Jewish, you will go to hell”.

I was very frightened and I missed my parents desperately. I refused to eat, could barely sleep, and kept together with my brother and sister. From Limoges we were taken, together with other children, by train to Lyon and hidden in another convent, before heading for a secret crossing point at the Swiss border. It was a difficult journey. Nazi officers prowled the crowded carriages. The Gestapo were everywhere. Near the Swiss border, close to the town of Annecy, our group of children were joined by a Jewish Girl Guide and French Resistance worker, called Marianne Cohn. She dazzled us youngsters with her smile and reassured us, “You will soon be in Switzerland. Don’t worry about the uniforms of the Swiss Army. They look similar to the Germans”. Tenderly she watched over us children and led us into a lorry. Together we were about thirty two children. Marianne told us “We missed the train, so I’ve organised a lorry to take us to our destination”. The driver didn’t know that we were Jewish. Later we found out that the driver was beaten up and, although he was set free, he died a few days later. He was only forty two years old.

In the lorry, my sister, Helen, swallowed the Swiss money that my parents had given us. She did so in case the Nazis would find it on us and would know that we wanted to cross the border.

That lorry would take us over the border. As we approached our destination, another lorry, full of Germans, suddenly appeared, their dogs barking and snarling at us. I clearly remember a boy in our group of eleven, who tried to escape. One foot actually over the border on Swiss ground, but he was shoed back by the dogs and thrown back into the lorry. He cried out, “I’m not Jewish! I’m not Jewish!”. Marianne and the driver of the lorry tried to reason with the Germans, repeating the story of a trip to a children’s holiday camp in France to escape the bombing in Lyon. Subsequently they left us alone, but when we arrived at Pas De L’Echelle, a little village at the Swiss border near Geneva, the Germans returned. We were questioned continuously, together with another child of nine, “Are you Jewish? Are you Jewish?,” they kept asking. We all found the courage to say no. It made little difference and we were sent to a prison called Prison Du Pax, where I, together with my sister and brother, was arrested and incarcerated. When we arrived there, my sister said to me, “You no longer need to save your dress for Shabbos now, because we’re all going to die”. After a couple of days in prison, my sister, my brother and I were taken by the Gestapo Chief Commandant Meyer and his associate to a big stark room for questioning. As we entered the room, on the right-hand side, we saw a boy lying all curled up on a plank, and had obviously just been beaten. We later found out he was beaten because he said he was from Nancy, and they knew that he had lied. To this day, I remember his name and face. Leon Sonnstein.

Chief Meyer stood in front of us, his gun pointing at our faces. He told us, “If you don’t tell the truth, you will be beaten like him”. He asked us, “Are you Jewish?” and we would answer, “No”. “What’s your name?” I would answer “Renee Blanchee”. “Are you Jewish? Where do your parents live?” I gave a false address. Again, “Are you Jewish?” and always it was a “No”. “What are the names of your mother and father?” I made up names. “Are you Jewish?” After that, he let us go and return to our cells. Every day, Marianne herself was taken away for questioning, returning each evening with a red and swollen face, having been subjected to hot and cold baths, amongst other forms of torture. He face became more deformed as time went on. She said to us, “Children, you must say everything”. After that, we were still there for another three to four days. Marianne never faltered or relented. She had opportunity to leave us, to save her own life, and to reveal our true identity, but she did neither. However, she was murdered by the Gestapo. They named a school in Annemasse after her. A tribute to her bravery in saving two hundred children.

Koenig children amongst crowd outside Annemasse Town Hall

In August 1944, about two weeks after our arrival, the Lord Mayor of Annemasse was able to negotiate our freedom. Members of the underground movement ‘Le Maki’ came and saved us. Those of us who were under the age of fourteen, my siblings and myself, were taken into Switzerland, to the Carlton Hotel in Geneva, which had been converted by the Red Cross into a refugee centre. After three months, my siblings and I returned home to my parents. We had been apart for six months. My parents managed to survive by going into hiding. My father felt that our survival had truly been a miracle.

As an adult now, when people ask me about my war time experiences, I feel I lost my childhood. I was only ten years old. I never found it again. I never learnt how to be truly carefree. When you are in hiding and when you are arrested, you live in fear and confront death every day and every minute. How could I have been a child again?

Still, with the love of my parents, I continued to have a normal upbringing. I worked for my father in his clothes shop and would often travel to Paris as his buyer.

As a young adult, a mutual friend introduced my future husband-to-be. He himself was a concentration camp survivor. The hesitation in marrying was that we were to live in Munich, in Germany.

My husband-to-be won me round.

Renee and Ernst’s engagement

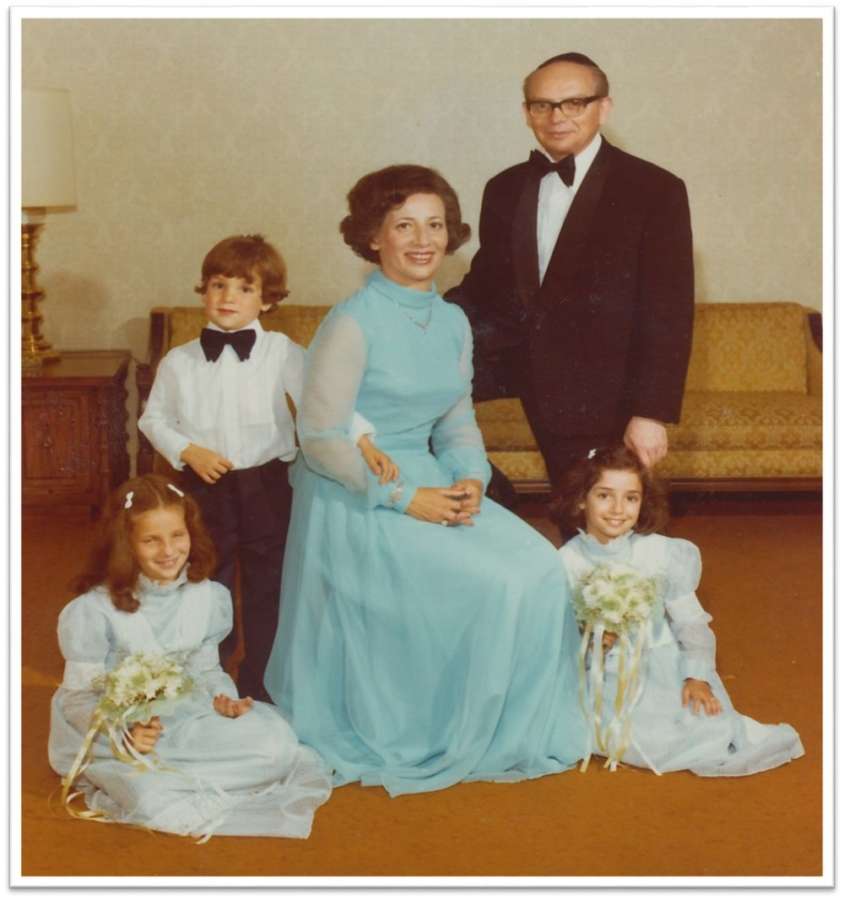

We married in France and settled in Munich, where my husband practiced as an oral surgeon and dentist. We had three children; two girls born in France and one son born in Manchester. Both my husband and myself had no hatred for the German people, so much so that our children had a wonderful, adopted German grandmother, called Meme Wolf.

Ernst and Renee’s family

My husband died in 1978. I was 44 years old and had 3 young children of 12, 11, and 7. Watching them through their tender years would always remind me of how young I had been when I went into hiding. The following year we moved to Manchester. With the warmth of the Manchester Jewish community, we were able to heal and I was proud to bring my children up with Jewish identities. Manchester is my home now, although I am still a frequent traveller to Europe and Israel.

My children married English spouses and gave me the precious gift of grandchildren and great-grandchildren, amongst them a soldier in the IDF and our very own dear rabbi. I thank GD every day that I survived to see the next generations and to be able to live in peace. Through my children and grandchildren, I found joy in life again. I was a child of the Shoah. My family is my victory.