When NOEMIE LOPIAN translated the harrowing chronicle of her father Ernst, a Holocaust survivor, she realised his trauma had impacted on her life, too. She tells Angela Epstein why she will always carry the guilt of her father’s suffering

Noemie Lopian has a clear recollection of the bookshelf in the living room of her childhood home in Munich: it was empty save for a solitary title on the middle shelf.

Yet as a girl, she resisted any urge to read it because she knew that something terrible was documented within its pages.

Spool forward three decades and Noemie, 49, has finally delved into her father’s memoir of his experiences during the Holocaust: an account of appalling suffering and inhumanity in seven concentration camps and five transit camps.

His parents and two of his siblings – from whom he became separated in 1941 – perished in Auschwitz. Of his immediate family, only one sister survived.

Moreover, Noemie, a former GP now living in Manchester, has spent the past four years translating Die Lange Nacht (The Long Night) into English from its original German.

‘For years and years, I couldn’t bear to look at it,’ she explains.

‘I didn’t have the emotional strength to face what my father had been through. I didn’t want to know the pain he had suffered.’

Until the outbreak of the Second World War, Noemie’s father Ernst Bornstein lived with his happy, close-knit family in the Polish town of Zawiercie.

All that changed when the Germans invaded in 1939: the synagogue was locked, Jewish pupils were outlawed from schools and the Nazis began their sustained policy of cruelty and prejudice towards the Jewish community.

For 17-year-old Ernst, life would never be the same again. Dragged away from his family and conscripted into forced labour in March 1941, he spent the next four years enduring physical and psychological torture, starvation and sickness, all of which he documents in his unflinching memoir.

At one point he describes breaking down after receiving a letter from his parents, passed on by a kind German soldier, telling him that their town had been ‘cleansed of Jews’ and that ‘like other transports before us we are probably going to the extermination at Auschwitz’.

In 1945, he was forced on a death march through Germany to evade the advancing Red Army; a friend who walked with him was shot dead by the SS when they arrived at the Gross-Rosen concentration camp.

Ernst was finally liberated in Bavaria by American soldiers on 30 April 1945. But there was no celebration for him – he spent the day beside mass graves filled with friends who had been killed just 24 hours before the liberation.

Later he discovered that of his extended family numbering 72 in 1939, only six survived the war including himself and his sister Regina.

Yet despite all of his traumatic experiences and devastating family loss, Ernst went on to train first as a dentist and then as a doctor after gaining a university place in Munich.

He established a successful medical practice and married Noemie’s mother Renée after meeting her through mutual friends when he was 42 and she was 30.

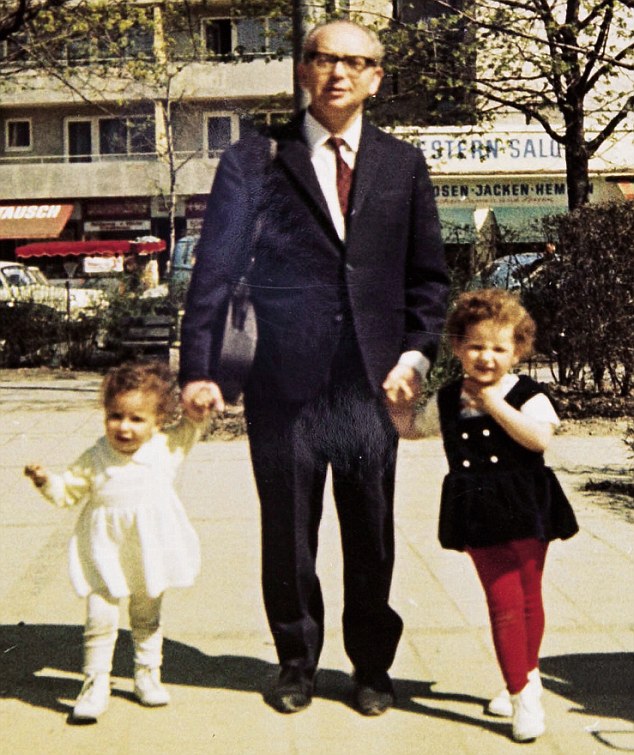

Sister Muriel, father Ernst and Noemie in Germany 1968 / 69. You. The Long Night. Noemie Lopian

He was also tireless in his work for fellow survivors, founding the Association of Ex-Concentration Camp Inmates in Munich and speaking every year at a memorial service at Dachau concentration camp.

I meet Noemie in her elegant Manchester home. Her parlour, with its family photos and restrained antiques, is redolent of a timeless European townhouse, despite being on the doorstep of the northern city she moved to 37 years ago.

Delicately pretty with wary, soulful eyes, she measures each word carefully as she reveals how she finally felt able to confront her father’s past.

As children, Noemie and her siblings – brother Alain, 44 (a lawyer living in London), and sister Muriel, 48 (who lives in Israel) – had a happy and comfortable upbringing in Munich.

‘I adored my father, and even though he often came home late, I would leap out of bed when I heard his key in the lock.

‘I loved spending time with him and relished our walks to the synagogue or to school, or Sundays in the park.

‘He’d tell me about his work and spoke about the women he knew who practised medicine. He made me believe that I had potential, that I could do anything.’

But even as children, Noemie and her siblings understood their father was different.

‘My mother was always protective of him,’ she recalls. ‘If he was having a rest we had to be quiet so he wouldn’t be disturbed.

‘My mother, who is French, had also suffered at the hands of the Nazis – she had been arrested and I questioned by the Gestapo at the age of just ten. But she never told my father her story as she didn’t want to burden him further.

‘My father was a kind, loving and brilliant man, who as a student had been prepared to sometimes go without food to fund his medical studies.

‘He never spoke to us of the horrors of the Holocaust, yet I realise now that what he experienced – even before I knew the details in his book – always walked with me.

‘It has shaped me, challenged me and, even though I sometimes lack courage and confidence, it has taught me about survival.’

Almost immediately after the war, Ernst began recording his wartime experiences. He wanted to chronicle the evils of the Holocaust while the details were still fresh in his mind.

Unlike many survivors of the time, whose wounds were too raw to revisit, he was driven by a need to educate young people in Germany, explains Noemie.

‘Especially since one of his young patients had thought – before meeting my father and being told the truth by him – that the gassing of women and children in Auschwitz was anti-German propaganda.

‘He saw the need to warn future generations about genocide and how it must never be allowed to happen again.’

Ernst’s testimony was published in Germany in 1967 – although it had previously been rejected by several publishers who exhibited little interest in revisiting their country’s bleak wartime past.

Yet it was well received on publication, netting a review in the Times Literary Supplement, even though it was published only in German.

In 1978, Noemie’s childhood was shattered when, at the age of 55, Ernst died suddenly of a heart condition – triggered possibly by the starvation and forced labour he had endured during his years of incarceration.

Noemie, brother Alain, Monterh Renee, father Ernst and sister Muriel. In New York for a wedding in 1974. You. The Long Night. Noemie Lopian.

A year later, the Bornsteins moved to England and settled in Manchester, where Noemie’s mother believed the warm Jewish community would offer the bereaved family somewhere to begin anew.

While Renée devoted herself to her children as a stay-at-home mother, Noemie and her siblings found themselves forging a new life in a strange country.

‘I was 12, my sister 11 and my brother seven when our father died, and I couldn’t wait to get away from Munich,’ recalls Noemie.

‘I naively thought that leaving Germany would mean leaving the pain of my father’s loss behind. But the thing about grief is it’s your travelling companion. It always comes with you.’

Eventually, Noemie won a place at Manchester High School, one of the city’s most prestigious girls’ schools, and went on to study medicine, as her father had done.

It was a significant achievement for a girl who had arrived in England unable to speak the language.

At the age of 20, while still at medical school, she married her businessman husband Danny, the son of a family friend, and less than two years later, in March 1988, she gave birth to their first child, daughter Orly.

As well as Orly (who now has three children of her own), Noemie and Danny are parents to 15-year-old twins Ella and Mia and to 13-year-old Nina.

In 2002, after Nina was born, Noemie gave up her job as a GP to become a full-time mother.

‘I just couldn’t juggle any more – I was pushing myself to the limit. But I felt disappointed in myself.

‘I thought of my father – how he’d had to choose between books and food to find the money to complete his studies – and felt I had let him down.

‘As a survivor’s daughter you bear the guilt of what they endured. I know so many survivors’ children who feel the extra pressure to succeed, to make up for what their parents had lost, but I just couldn’t do it, I had to put my family first.

‘Also, I couldn’t ever be what he had been. He set the bar extraordinarily high. He was more than just a doctor. He had a calling to help anyone and was indefatigable in that.’

Having given up work, Noemie found herself drawn to her father’s book. She felt the time had come to engage with him, adult to adult, and to hear his voice again.

Reading it in one sitting, she recalls, was gruelling, especially since Ernst recounts the horrors of the Holocaust and of his daily existence in unsparing detail.

But this narrative of human suffering has also helped Noemie see another dimension of the father she still misses.

‘For example, when I was a child, one of my father’s German patients, a non-Jewish lady, was widowed. So our family adopted her as a grandmother figure. I didn’t think anything of it.

‘As children you accept things as they happen. But now I realise the magnanimity of my father’s gesture.

‘After everything he had been through, it would have been so natural to have antipathy towards Germans like this woman.

‘It made me understand my father’s humanity, which wouldn’t allow him to do anything other than care for people. I really appreciated his faith in the goodness of others.

‘To me, as a child, he had simply been a wonderful papa. As an adult I understood he had been an exceptional human being.

‘There are so many questions that I would like to have asked him. How, for example, did he find the heart to treat his German patients so soon after the war – even when they often couldn’t pay him?’

After reading the book, Noemie felt she had to tell the world about her father’s experiences. So she secured the services of a co-writer, David Arnold, to help her translate it.

‘Weighing up every word my father had written was painful but cathartic. I could hear his voice in my head and it made me love, admire and miss him even more – it was like grieving all over again. His suffering has made me acutely aware of life’s challenges and fragilities.

‘I realise that I have been so blessed with Danny, a wonderful husband and father, and with our four daughters and our grandchildren.’

Even today, she has never lost the haunting fear that it could all be taken from her.

‘Now anti-Semitism has become more overt we have to make people aware of what happened to those like my father. I worry for my children and grandchildren being attacked simply because they are Jewish.’

Whenever the translation work became so painful that she couldn’t continue, one particular passage from the book always gave her strength. It relates to Ernst’s little brother Yehuda who was murdered at Auschwitz.

Her father wrote: ‘I will continue to write because my little brother’s voice is still ringing in my ears; because you were suffocated, you with your happy heart, with your serious child’s eyes with which you watched over my shoulder as I was reading.

‘For you dear brother, with your innocent eyes which were barbarically extinguished in Auschwitz. You look at me in the darkness when I lie awake and your eyes warn me, “Don’t forget!” For you I will have sleepless nights, my little brother. For you I will tell the story of the long, bloody night.’

Noemie has done what she can to ensure the story continues to be told. She devotes her time to promoting Holocaust education – and is a key member of the committee that stages Manchester’s annual community-wide Holocaust commemoration service.

‘I know I can never measure up to my father; but I can carry this baton of remembrance for the six million who were murdered by the Nazis.

‘This hasn’t been about self-pity; it has been a journey of self-discovery. Commemorating the Holocaust isn’t enough.

‘We have to educate each new generation, so that such horrors never happen again, and we must continue to seek out and believe in the good of humanity. I learned this from my father years after I lost him.

‘It’s a message I want to spread in his memory and share with those who will listen.’